Sitting on both sides of the Suffolk/Norfolk border, the rivers Waveney and Little Ouse are responsible for much of the county boundary and are an important part of the local East Anglian landscape connecting the Broads to the Brecks.

We are all familiar with the gentle, or not so gentle pitter patter of rain against a window—a precursor to water eventually accumulating in a nearby floodplain. This year that floodplain is already fully saturated following a winter of high intensity rainfall.

Farmers and landowners in our local area are providing floodplain water storage, thereby safeguarding populated areas within the Waveney and Little Ouse catchments from flooding. This water storage may reduce financial viability of floodplains, reducing available pasture for livestock.

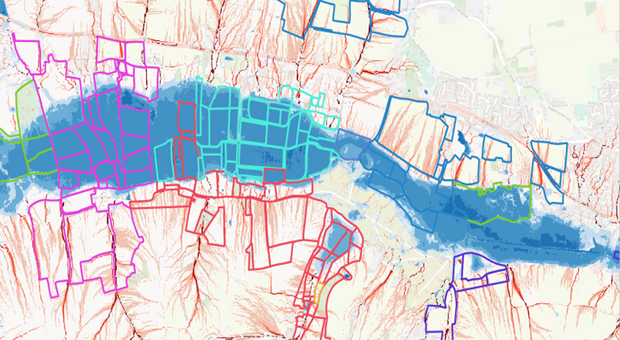

Our Landscape Recovery project, the Waveney and Little Ouse Landscape Recovery Project, sits on the headwaters of the 2 rivers, covering over 1,600 hectares between the towns of Diss on the Waveney and Thetford on the Little Ouse.

We want to improve the habitats associated with floodplains: from poor quality grazing grassland to functional fen, which can absorb more water into the ground, meaning less water moving downstream and at a slower pace, reducing the risks of flooding through the catchment.

The creation and maintenance of reedbed and fen habitats also provide a natural water cleaning service which should improve the overall quality downstream of the project on both rivers.

The project seeks an opportunity to realise the invaluable services our floodplains provide. Currently, these areas are not designed to be flooded, with historic networks of drainage ditches made to move water out of the area to increase land productivity.

Led by Suffolk Wildlife Trust, our project is now over halfway through the project development phase which ends at the end of 2024.

We’re working with 17 farmers/landowners to deliver environmental benefits both on-river and off-river. This includes devising methods for storing water more effectively in the wet months, utilising it to maintain moisture in peatland soils that currently release carbon in dry summer months, and to revive diverse wetland ecosystems conducive to thriving nature.

Outside of the floodplain, we aim to improve the water quality by changing land use and how the land is managed, to reduce the nutrient and pollutant inputs into the river.

Within the floodplain, our challenge is to restore valley fen habitats.

We want to return these habitats to their historic function, as both carbon sinks and flood mitigators. We look to restore the river itself from a cut channel, to a more naturally meandering composition, with graded edges to allow water to spill into the floodplain and slow water movement downstream.

Some of the recommendations made so far are to slow water arrival from the wider landscape to reduce ‘flashy’ water accumulations, retaining winter water in the right areas throughout the year.

We also aim to provide landowners with viable business opportunities in providing ecosystem services which benefit their farming businesses, the climate, the environment, and local communities engaged with a restored landscape.

In this post, I’ll share our work so far: our achievements and challenges and how we’re turning an idea on paper into action.

Our first year

When I became project manager in January 2023, I knew it would be quite a job, but even then, I had no idea how multifaceted the task ahead was.

Reflecting on a year’s work, I’m pleased with the progress we’ve all made.

Prior to the beginning of the project, back in 2021, a study was completed to gather information on the natural assets of the landscape. This formed the basis and vision of our application.

In 2023, we established a baseline of the natural capital in the landscape, through a series of surveys and models. We’ve worked closely with farmers and landowners to create a thorough plan to improve nature in the catchments.

Through Landscape Recovery, we are looking to secure finance from the private sector to fund our plans. To help with this, the project has quantified several ecosystem services that are calculated against our project uplift plan:

Alongside the more familiar territory of planning habitats for the environment (at least for me as a conservationist), we have also been planning our engagement with the local community.

We’ve run a series of small events and surveys, and we’re excited to learn more about how our project can better engage people with their local environment.

As a group of landowners, farmers and food producers, the impacts of nature-based land-use choices on productivity are something we need to consider seriously.

Financial viability will undoubtedly shape which options are best, and where we have arable land that we want to continue to farm, we are working with landowners on encouraging a regenerative agriculture approach, with fewer chemical inputs and measures which will improve soil and water health alongside biodiversity.

We have a mix of landowners, some putting forward low-productivity land where making profit is tricky, and some allowing us to explore land-use changing options on higher-productivity land to determine if it is profitable.

During the latter half of 2023, we began to build relationships with potential buyers and investors in our project, building our private finance approach.

From the start of 2024, most of the market interest in our ecosystem services focuses on carbon, with a wider interest in biodiversity and hydrology, specifically with floodwater storage. We are co-developing this approach now with landowners and funders, seeking a financially sustainable approach that is free of greenwashing.

Year 2

This year will determine the success of our project, as we begin to receive financial backing and prepare for negotiations on the terms and conditions for the sale of our natural capital and ecosystem services.

We’re working hard to pull together the delivery costs of the project for the duration of an agreement, which may span over 20 years.

We will conduct several baseline surveys as part of our monitoring, evaluation and learning plan, from species surveys to social engagement recording.

We want our work to be more visible so we’re creating more of a social media presence and conducting in-person talks across the country. You can follow our progress on X.

One of the remaining challenges, alongside finding the right finance package, is the length of time it may take to gather and agree the right legal permissions to deliver our uplift plan.

We’ve identified over 40 permissions for the project from the Environment Agency, Natural England, local planning authorities and other bodies.

We know that the ask for time from our project is significant. We'll continue to work with Defra on an appropriate approach to permissions that opens the process, but don’t remove environmental protections.

Reflection

Landscape Recovery presents a great opportunity to encourage widespread nature recovery in England.

It’s important to say that being able to build a functional model that puts nature first could act as a template for future similar projects across the county and, indeed, country.

We think that if we can get this right, the Waveney and Little Ouse Recovery project has the potential to expand beyond its current boundaries to provide financial security through nature recovery both downstream and throughout the catchment.

If you’d like to learn more about me, our project or the area, visit our project page on the Suffolk Wildlife Trust’s website. Or, if you have a question, you can leave it in the comments below.

The

The

Leave a comment