If you want to encourage more of the right wild plants and insects on a group of farms, what parts of your farm should you target to get the best results? This is the question conservation scientist Dr Robert Hawkes explored with colleagues from the University of East Anglia, the Breckland Farmers Wildlife Network and Defra.

Back in early September, Esther Rosewarne described how Defra had been running tests and trials with the help of groups of farmers working collaboratively on environment projects.

One of the groups Esther mentioned was the Breckland Farmers Wildlife Network in East Anglia - a collective of 52 farms over more than 44,000 hectares, working together to "create a landscape-scale wildlife network".

Many farmers collaborating at this sort of scale can make a big difference with the right approach to managing hedgerows, field edges and other habitats.

I'm not a civil servant, I'm a scientist. I've recently been part of a team from the University of East Anglia, working with colleagues at Defra and the Breckland Farmers Wildlife Network to take a closer look at some of the specifics of good agri-environment schemes.

We already know that collaborative groups of farms are a good way of bringing about landscape-scale change, but we wanted to build on existing knowledge about what species to conserve and which options best suit their needs. In particular, we wanted to know where to prioritise effort.

To put it simply: if you want to encourage more of the right wild plants and insects on a group of farms, what parts of your farm should you target to get the best results?

If implemented correctly, answering this question would allow us to achieve better, bigger and more joined up conservation on a landscape scale – an important aspiration, but one that is rarely achieved in practice.

The answers are found in maps

Using a paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology which describes the species found in our region and their management needs, our team designed a tool that generates maps covering individual farms, small groups of farms, or the entire Breckland network.

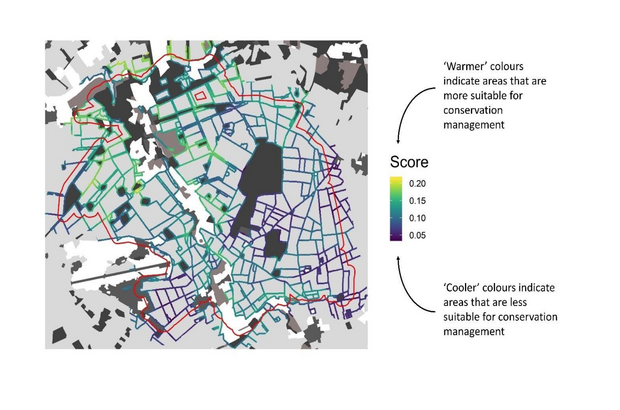

We focused on a group of over 500 rare, scarce and threatened invertebrates and plants that benefit from a specific field margin management technique (cultivated but uncropped margins). The results look like this:

This map shows boundaries of arable fields on a single farm. The "warmer" green and yellow colours are places that are more likely to support priority plant and insect species. The cooler purples and reds show areas where those species are less likely to occur.

On this farm, the model shows that it would make more sense to focus specific efforts in the upper-left corner of the map, where the warmer colours show up more.

As part of our work, we provided every member of the Breckland Farmers Wildlife Network with their own bespoke version of this map.

It’s important to mention that we were only able to create this tool thanks to the phenomenal amount of wildlife records collected by experts and enthusiasts over the past 40 years.

This is the start of something useful

Encouragingly, most of the Breckland group members said that this mapping tool was useful for them, and they were more likely to engage with coordinated landscape-scale conservation as a result of this test and trial. However, maps alone are only part of the solution.

For many of them, the crucial detail is the payment rates they will get for delivering options in schemes like this.

On some farms, if those payments aren't competitive, the conservation work is unlikely to go ahead. This would prevent our blueprint from turning into a reality.

Another finding from our year-long test and trial was the value of so-called "mini-clusters": groups of farms working together on a smaller scale on a day-to-day basis – as a way of coordinating a much larger cluster group. There's more research to do on this and other matters, and we're hoping to explore this in finer detail through a follow-up test and trial.

One thing we can say is that we think this model would work well in other places, so it could be scaled up to help other groups similar to the Breckland Farmers Wildlife Network. The essential ingredient is the detailed wildlife data for local areas, combined with knowledge about their management needs, and that is freely available across the country. The same approach could be used more widely for only a modest cost.

By highlighting the best areas wildlife conservation through a simple set of maps, we think this approach can empower farmers with the knowledge that their agri-environment actions will genuinely deliver, and in doing so, improve the sector's contribution towards nature recovery.

If you have any questions about my team's work with the Breckland Farmers Wildlife Network or questions for Defra colleagues, do comment below.

The

The

7 comments

Comment by Helen Rhodes posted on

Thanks for this, I for one, as a long term 'stewardship' farmer am intrigued by this. Firstly, what is the scale of the map? How big are the fields, do the boundaries that are less favourable have hedges, and if they do how healthy are they?

I was immensely frustrated when signing up to HT in 2018, to find that the arable plant assemblages listed were largely from the Southern part of the country and had no relevance to us. To take this further, I note your comment about being dependent upon good existing records, in our area, due to the large number of nature reserves, there is little, or no recording done on farms, even arable bird assemblages are focused on the wetlands nature reserves, so lack of records could potentially result in lack of opportunity if past systems are anything to go by.

I am interested to know what features make for the more favourable areas, is it topography, adjacent habitats or other factors? Presumably different plant/invertebrate assemblages will trigger differing favourable areas? Could this then work against those things that don't fit in with the norm for the area?

Whilst I admire the work going into making ELM work, is this not putting the cart before the horse? By which I mean telling you what is or is not going to occur in your area and then zooming in on this. Would it not be better to get a broad range of options in place across the country (obviously with a general targeting) and then have Natural England (or similar) advisors on hand to review success of various elements and refine agreements accordingly allowing them to evolve to create maximum benefit.

It would seem to me, but I could be wrong, that the research you have done here is effectively doing that in order to create hard and fast templates that Elm agreements are going to have to be shoehorned into.

I genuinely want my stewardship to work as well as it can, and after nearly 30 years we feel we have a fair idea of what works and what doesn't (on our farm I would stress). For years I have been trying to convince whoever I can that funded surveys should be part of any stewardship scheme, how else is their success going to be measured? Add to this the fact that your work here has been dependent on surveys I struggle to understand why they are not.

A successful scheme for working with nature and environmental factors can never be tied down to an inflexible set of prescriptions, what works in one place may not in another, and may vary for year to year. Having been optimistic that ELM was going to work more flexibly than the dire office-based scheme we currently run, this worries me that we are once again going down the rabbit hole of fixed rules.

Let's operate something along the lines of your research as part of the scheme as it runs. Surely there are plenty of universities with ecology and other such students keen for ongoing recording and feedback into improving what is happening. Maybe this is an opporunity for defra to fund collaborative projects between land managers and schools / universities?

Comment by Amanda Hughes-Horan posted on

This is an amazing resource- so exciting to see this map. Kudos to everyone for their hard work on the ground to guide this test and trial process. Wonderful to see it come together and wishing you the very best for future collaboration in the field,

Amanda Hughes-Horan

Interpretive Insights

Comment by James Hedger posted on

Thank you. An interesting approach. It is important to look carefully at your farm. We commissioned an ecology survey this summer on our farm in Devon. It cost £250..... a rare blue beetle was found [pondweed leaf hopper] only seen in 3 ponds in Kent before now. Hopefully DEFRA will fund such surveys and land owners will welcome them and the results will be made publicly available somewhere......where should the information be deposited?

Comment by J Barnes posted on

It’s not just positive encouragement by decent payment rates for ‘interested’ farmers. There needs to be serious disincentives for those many farmers who just aren’t interested. We all know them and there needs to be some serious reduction in the payments for the ‘easy’ money. I.e. the BFP we get now for just turning up.

Comment by Janet Maxwell posted on

This all sounds great. But what is the difference between this and the Local Nature Recovery scheme we are waiting for details about. We are working up a proposal for a pilot project for the LNRS across the Culm Grassland in West Devon building on the work of the Local Wildlife Trust team and the mapping using magic maps is a vital part of this so would like to hear how we can access the mapping you describe and species element and who does it and how they can be paid at this early stage.

Comment by Tony Powell posted on

I like this approach, I'm not a farmer, but I work with them independently as a bird and farmland wildlife researcher. They (landowners, farmers, etc.) will often provide me with maps of their own farms, so it's second nature to them to use mapping approaches. Together, we can target fields or woodland blocks and the like, which we believe would be worthy of my surveying efforts. The ongoing reporting of the data and any other observations I make are crucial to the sustainability of their farming businesses as well. Just like them, I improve my knowledge by "walking the land". Not only that, but keeping tabs on all the latest scientific evidence pays dividends as well. Wildlife data gathering is never a static task and is constantly being added to. In my game, new bird species are being recorded on-farm every year that passes. That in itself proves the farms involved could well be making great strides towards broader nature recoveries in the long run.

Comment by Karen Lindley posted on

I note your comment regarding the need for a ‘competitive’ payment rate. What was considered competitive by the participants? Was this judged against existing funding for similar land management or based on income forgone for an individual's circumstance?